Thomas Barnard, writer

▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀

Home

Writing

Articles

Artifacts

Contact

c2003-2009 Thomas Barnard

The Secret Six

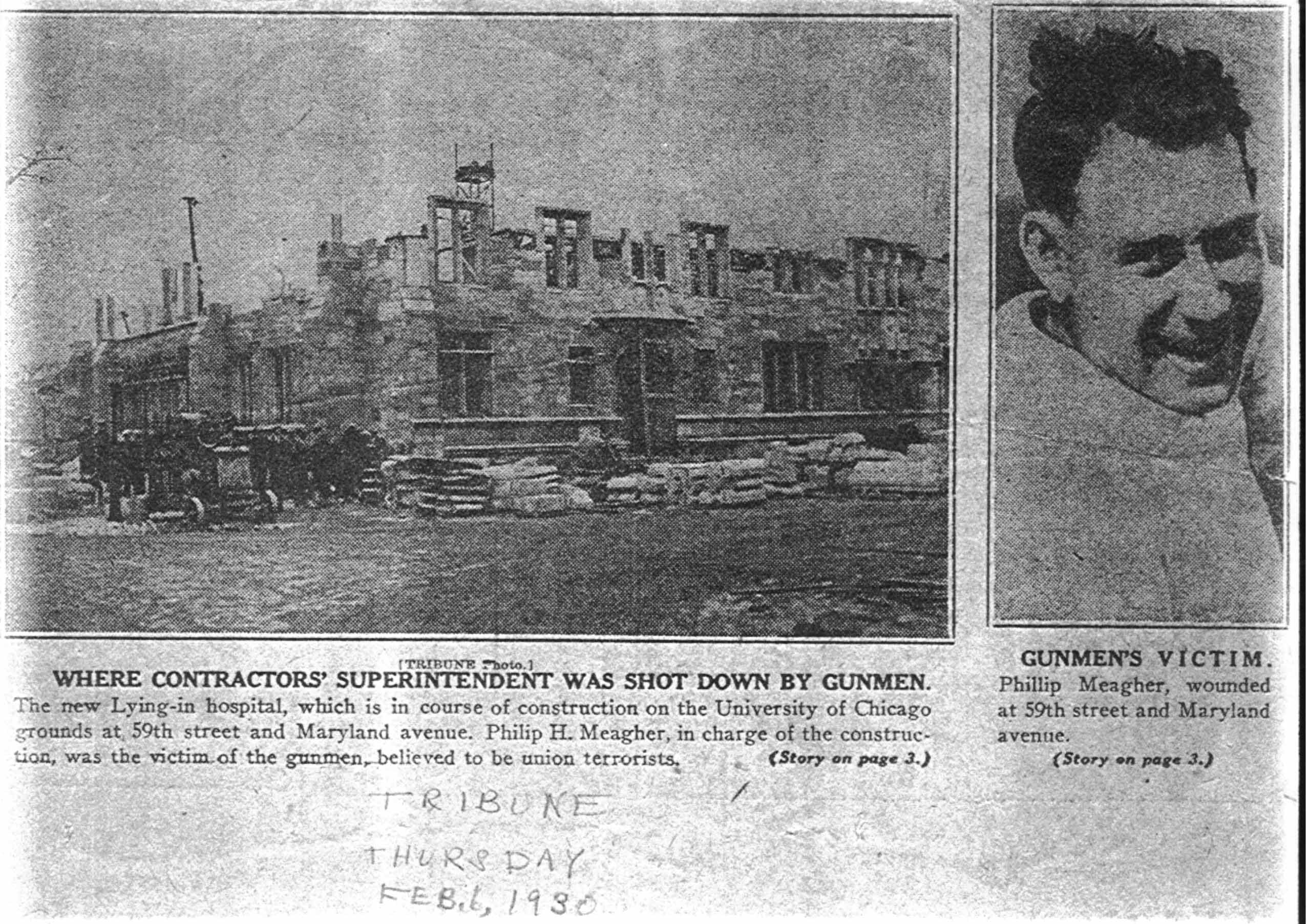

On February 5th,

1930, a black sedan pulled to a stop at the curb of the construction site of the

Lying-In Hospital on 59th Street. A laborer who had been hired two days

before ran to the sedan, crossing in front of it, took a position on the running

board and shot across the front of the car at the job superintendent, Philip

Meagher. He emptied the gun at him. Two of the bullets hit

struck

Meagher in his chest, a third and fourth went through brim and crown

of his fedora, the other two struck the building. The job foreman, Slim

Ebert,

pulled him down

behind a pile of

bricks. According to the final edition of the papers that night, Meagher

was not expected to survive.

bullets hit

struck

Meagher in his chest, a third and fourth went through brim and crown

of his fedora, the other two struck the building. The job foreman, Slim

Ebert,

pulled him down

behind a pile of

bricks. According to the final edition of the papers that night, Meagher

was not expected to survive.

This shooting triggered a chain of events which

led to the arrest, trial, and imprisonment of Al Capone. The

evidence for how that shooting led to

Capone’s downfall is sparse, fragmented,

and shrouded in secrecy. But some of the facts can be pieced together. Meagher

was targeted because his employer, the H.B. Barnard Company, was accused of

using non-union workers. It is thought that the union

invited gangsters to help out.

Capone’s downfall is sparse, fragmented,

and shrouded in secrecy. But some of the facts can be pieced together. Meagher

was targeted because his employer, the H.B. Barnard Company, was accused of

using non-union workers. It is thought that the union

invited gangsters to help out. Usually, gangsters targeted each

other and the civilian population went

unaffected. This time they violated the unspoken rule, and by now the

business community was fed up and ready to

act.

Usually, gangsters targeted each

other and the civilian population went

unaffected. This time they violated the unspoken rule, and by now the

business community was fed up and ready to

act.

Meagher's employer was builder

Harrison Barnard, and he led the charge. Barnard was a prominent builder who

had built the Chicago Theological Seminary, Frank

Lloyd Wright's Robie House,

and was a trustee of the University

of Chicago.

He lacked faith in the

police department because so many were known to be on Capone's payroll. So, the next day

he went downtown to the Chicago Association of Commerce, where he was a member

and brought the matter to the CAC president, Colonel Robert Isham Randolph.

Barnard pointed out that many contractors were members, and argued that no one knew who

would be marked next. The police were obviously ineffective, and shooting his

employee was an unacceptable negotiating tactic in an attempt to

re-establish the closed shop in Chicago's building trades. He put up $5,000 of

his own money as a reward for information about the people who shot on Meagher.

of Chicago.

He lacked faith in the

police department because so many were known to be on Capone's payroll. So, the next day

he went downtown to the Chicago Association of Commerce, where he was a member

and brought the matter to the CAC president, Colonel Robert Isham Randolph.

Barnard pointed out that many contractors were members, and argued that no one knew who

would be marked next. The police were obviously ineffective, and shooting his

employee was an unacceptable negotiating tactic in an attempt to

re-establish the closed shop in Chicago's building trades. He put up $5,000 of

his own money as a reward for information about the people who shot on Meagher.

I grew up hearing about the Secret Six because Harrison Barnard was my

grandfather, and Lying-In Hospital, where the Meagher shoot ing

occurred, was the place of my birth. Meagher, who the papers claimed was

not expected to survive, lived on the same street I grew up on, Prospect Avenue

in Beverly Hills, and continued as my father's superintendent after Harrison

died, finishing his career by directing the construction of our house in

Hinsdale in 1958.

ing

occurred, was the place of my birth. Meagher, who the papers claimed was

not expected to survive, lived on the same street I grew up on, Prospect Avenue

in Beverly Hills, and continued as my father's superintendent after Harrison

died, finishing his career by directing the construction of our house in

Hinsdale in 1958.

The story as I have it from Harrison

Barnard’s two living children, William and Burton, was that Barnard’s wife,

Elizabeth, was so outraged about the shooting of Meagher and so worried about

her own family, that she insisted her husband do something. She walked the

floors all night, wringing her hands, which her children remember, and her

husband acted in the morning. There’s the origin of your civic action.

**

The CAC met with Cook County State's

Attorney John Swanson and Police Commissioner William Russell at the LaSalle

Hotel on February 11, 1930. Swanson provided important guidance:

“I have a large staff of

investigators, but everybody knows who they are. Their names and addresses are

printed on the roll which is a public document and it is very difficult for a

man under such circumstances to get the kind of information that we need to

secure conviction in criminal cases. Now, if you gentlemen want to be helpful,

I suggest that you undertake to organize a real secret service, in which no one

knows who the operators are and in which perhaps the operators themselves don’t

know each other, and have all these operations head in through one man, and the

complete operation only known to him. So much of it as he cares to reveal to

the States Attorney, he can give to him. If you can supply these operators with

money enough to run with the wolf pack and buy information from the jackals that

trail the pack, if you can provide funds for the protection of witnesses and do

for the State’s Attorney the things he can’t do for himself, you can get the

kind of information we need to secure convictions; and with that information,

any of the seventy-odd assistant state’s attorney on my staff can get

convictions and without it the best lawyer in the city can’t”

So, a "power lunch" was held the next

day at the Mid-Day Club. Among those who attended the meeting were George

Paddock, a stockbroker, Frank Loesch, a lawyer, Edward Gore, a public

accountant, and Colonel Randolph. Also attending was Julius Rosenwald,

president of Sears Roebuck, who had already given money against crime with no

discernable effect, but who, nevertheless, he agreed to put up $25,000 with an

open door to return if they produced results. Finally, Samuel Insull attended

the meeting and promised to meet up to 10% of any amount raised.

This was when financial titan Insull

was at his apogee. The Lyric Opera House Building, which was his pet project,

was completed in 1929. Some joked that it was shaped as a throne for Chicago’s

empire builder. And he had just financed $200 million of construction money for

Commonwealth Edison with bonds. Insull, a Scot who had come to America to be

the personal secretary of Thomas Edison, had gotten in on the ground floor of

the build-out of the huge project of bringing electricity to the people.

How much was raised at this initial

meeting? Four people put up $25,000 (one them we know was Julius Rosenwald).

Samuel Insull made the largest contribution, $35,828.60, and 803 contributors

gave an additional $71,189.28. This totals $207,017.88.

However, if Insull's contribution was

10%, then maybe the total sum was closer to $350,000. Though Randolph told

reporters on February 20th that funds were unlimited, running to $1,000,000. A

remark perhaps calculated to put the gangsters on notice that they weren’t the

only force in the city.

That there were 803 other

contributors shows that business was united, and this made for an unrelenting

force. The business community was determined to be rid of this hindrance to

normal life.

Randolph announced the formation of a

subcommittee of the CAC to deal with crime on February 18, 1930, thirteen days

after the shooting of Meagher. Randolph said he had chosen "men of courage" to

battle Chicago's gangsters, but when asked who they were, he declined to divulge

their names, so James Doherty of The Chicago Tribune dubbed them "the

Secret Six."

These events occurred about five months after The

Crash, and newspaper accounts say the police had not been paid for weeks, so

they had little motivation to help out.

The big question is what effect did

the Secret Six have? What exactly did they do? Because they were really

secret, this will never be entirely known. Meagher was shot on February 5,

1930. Al Capone was convicted of tax evasion on October 17, 1931. It took

roughly a year and a half to acquire the information to put away Big Al.

We know they hired as director,

Alexander J. Jamie, who was then the Chief Special Agent of the Department of

Justice for the district, and Randolph had to go to the President himself to get

a leave of absence for him to head up the organization. And Alexander Jamie’s

brother-in-law was none other than Eliot Ness. Ness was counting on Jamie to

get him the assignment he wanted, to harry Al Capone with a small group of his

own.

Ness’s book The Untouchables

begins with Colonel Randolph speaking before the Secret Six: “There is no

business, not an industry, in Chicago that is not paying tribute, directly or

indirectly, to racketeers and gangsters. I know you gentlemen agree that we

must spend any amount of money necessary to put these hoodlums where they

belong.”

Of the Secret Six themselves, Eliot Ness says,

“These six men were gambling with their lives, unarmed, to accomplish what three

thousand police and three hundred prohibition agents had failed miserably to

accomplish: the liquidation of a criminal combine which paid off in dollars to

the greedy and death to the too-greedy or incorruptible.”

Brother-in-law Alexander Jamie met with Colonel

Randolph, and Randolph leaned on U.S. District Attorney, George Emmerson Q.

Johnson. Johnson gave Eliot Ness, Ph.D. from the University of Chicago, license

to get his nine men. Eliot then proceeded to bust up stills and acquire

evidence.

In one of his first moves, he showed just how

unreliable the police were by having a decoy picked up by police, who sold him

some hootch while in the clink. They turned the offending policeman to get his

supplier.

The gangster lost no time in trying to bribe

Ness. They sent him two crisp one-thousand bills, and said he could have that

every week, if he’d lay off. The press got ahold of that news and one story

opened, “Eliot Ness and his young agents have proved to Al Capone that they are

untouchable.” Thus, The Untouchables were born.

Meanwhile the

Secret Six set up a speakeasy in Cicero known as the Garage Cafe deep in Al

Capone's backyard to acquire information about bootleggers. The place was run

by Sam Constantino (alias Frank Galgano), and Pat Horan, an undercover policeman

with the Chicago Police Department. They paid $100 up to $1,000 for information

to low level members of Capone's operation.

The speakeasy was in operation for

six months when Constantino came to Randolph, afraid that he'd been found out,

and said, "I'm takin' it on the lam. Here's the keys and I'm goin' and goin'

for good." Constantino, like many in the double world of spies, ended up

sentenced to three months for fraud. And later still, in 1937, he was sentenced

up to seven years for running an interstate stolen goods ring.

Secret Six money was spent on things

for which the government could not or did not have the money to pay for.

For example, the U.S. Treasury

Department discovered that Al Capone had never filed an income tax return, which

might appear on the surface to have been an easy case, but they did not have the

evidence to prosecute a case on it. This was in the long ago time before

deficit spending became a habit. So, the Secret Six made available $75,000 to

make the income tax case, no questions asked. The money was spent by Federal

agents Frank Wilson and Pat O'Rourke.

O'Rourke bought gaudy clothes - a

white hat with a snap brim, several purple shirts and checked suits, rented a

room at the Lexington Hotel, hung out in the lobby, and played the dice game

known as the "Fourteen Game." Meanwhile, Wilson checked into another hotel and

started pouring over books seized by local authorities.

Nobody wanted to talk about Al, so

Wilson told his boss, Elmer Irey, that he wanted to get Frank Nitti, "The

Enforcer," and Jake Guzik (Capone's right-hand man), "The Little Fellow," out of

the way. With them out of the picture, others might talk.

They got Nitti for endorsing a check

which Wilson knew was part of the receipts for a Cicero gambling operation. In

March of 1930, Nitti was charged with making $742,887.81 for the years 1925-27

without paying any tax. The indictment was evidently not kept secret enough,

and Nitti went "on the lam" and disappeared.

They worked the same case against The

Little Fellow. Guzik had signed checks and was collecting profits from a

gambling operation called The Ship. Fred Ries was the cashier at The Ship.

Ries, who initially had been detained in a prison cell for protection, was sent

to New Orleans where he boarded a steamer to South America for a ninety-day

voyage at the expense of the Secret Six, who gave the Treasury Department

$10,000 to pay for his protection.

Guzik was arrested on September 30,

1930; on October 3 he was indicted, and on November 19th he was convicted.

Capone’s world was now getting

smaller. With The Enforcer, Frank Nitti, gone and the Little Fellow, Guzik,

soon off to prison, The Big Fellow wanted a meeting with spokesman for The

Secret Six, Colonel Robert Isham Randolph.

Randolph's scrapbooks tell the story

of how Guzik asked Randolph if he would come to a meeting with Capone. Randolph

agreed. This was February of 1931, Guzik called back, "This is the Little

Fellow. I have the Big Fellow planted in a hotel near the Loop where you can

talk to him without being seen. Will you go?"

Randolph again agreed to meet with

Capone. This was bravery beyond the call of duty. No time to acquire a police

tail, he followed instructions to meet with Guzik, and then Guzik delivered him

to Capone's place of business, the Lexington Hotel.

Entering through the rear, they went

up in a freight elevator. They passed numerous gunmen before reaching Capone's

suite. The Big Fellow came from behind his desk and greeted Randolph.

"Hell, Colonel, I'd know you anywhere

- you look just like your picture."

Randolph smiled, "Hell, Al, I'd never

have recognized you - you are much bigger than you appear to be in photographs."

Randolph took off his coat and handed

him the .45 caliber pistol that he carried for protection. Capone placed it on

a chair.

"May I use your telephone? You see,

your name has been used to frighten women and children for so long that Mrs.

Randolph is worried about me; she knows of my visit. I would like to call her

and tell her everything is o.k."

Al respond, "Women are like that."

When Randolph came back, Capone

served him a beer and asked, "Colonel, what are you trying to do to me?"

"Put you out of business."

"Why do you want to do that?"

"We want to clean up Chicago, put a

stop to these killings and gang rule here."

"Colonel, I don't understand you.

You knock over my breweries, bust up my booze rackets, raid my gambling houses,

tap my telephone wires, but yet you're not a reformer, not a 'dry.' Just what are

you after?"

And before Randolph could answer,

Capone continued, "Listen, Colonel, you're putting me out of business. Even

with beer selling at $55 a barrel, we didn't make a nickel last week. You know

what will happen if you put me out of business? I have 185 men on my personal

payroll, and I pay them from $300 to $400 a week each. They're all ex-convicts

and gunmen, but they are respectable businessmen now, just as respectable as the

people who buy my stuff and gamble in my places. They know the beer, booze, and

gambling rackets-and they're old rackets, rackets that sent them to the can. If

you put me out of business, I'll turn every one of those 185 respectable

ex-convicts loose on Chicago."

"Well, Al, to speak frankly, we are

determined to put you out of business. We are burned up about the reputation

you have given Chicago."

"Say, Colonel, I'm burned up about

that, too. Chicago's bad reputation is bad for my business. It keeps the

tourists out of town. I'll tell you what I'll do: If the Secret Six will lay

off my beer, booze, and gambling rackets, I'll police this town for you - I'll

clean it up so there won't be a stickup or a murder in Cook County. I'll give

you my hand on it."

Randolph refused to go along, but he

did drink another glass of beer.

Capone asked, "Say, Colonel, what do

you think about the mayoral election? Should I come out for Cermak or ride

along with Thompson?"

"I think you better stick with 'Big

Bill.'"

Randolph put on his coat and hat, and

Capone handed him back his pistol saying, "So even respectable people carry

those things?"

Then Al shook Randolph's hand and

said, "No hard feelings?" Randolph replied, "No hard feelings."

The trial came off worse for Capone

than it ever should have, with his attorney failing even to protest the

introduction of evidence. Of course, Capone did not rely entirely on his

lawyers -- he bribed ten of the jury. But that was undone when the judge

switched juries at the last minute.

In a July 30, 1931 interview

published in the Chicago Herald Examiner, Capone said, "The Secret Six

has licked the rackets. They've licked me. They've made it so there's no money

in the game anymore." He was 32 years old.

Well, it's hard to believe that

someone of Al's character ever thought he was licked. He would be in the clink

for a few years, then it would be back to the bigtime. But it's understandable

that he would point his finger at The Secret Six as his nemesis because it's a

sure thing he wasn't afraid of the police.

**

Alexander G. Jamie, who was the chief

investigator for the Secret Six and a former prohibition agent, claims the

Secret Six handled 595 cases and aided in 55 convictions, with sentences

totaling 428 years. Fines of $11,525 had been paid, and they recovered

$605,000 in bonds and $52,850 in merchandise. The Secret Six handled 25

kidnapping and extortion cases in which nine convictions were made.

**

It was an age

of scrapbooks. My Mom kept a scrapbook of her Hollywood stars, my grandfather

Harrison Barnard kept a scrapbook, and Colonel Robert Isham Randolph kept a

scrapbook.

Randolph's scrapbook provides perhaps

the best evidence of the effectiveness of the Secret Six, but in my grandfather

Barnard's, there are newspaper clippings and the threatening letter to his

carpenter foreman Slim Ebert. Recently, and the proximate cause for writing

this article, my stepmother found this note in one of Harrison Barnard's

scrapbooks next to a newspaper article, "I was one of the Secret Six - HBB." He

never admitted his membership in the Secret Six to any family member in his

lifetime. So this ended sixty years of speculation among family members about

his role.

article, "I was one of the Secret Six - HBB." He

never admitted his membership in the Secret Six to any family member in his

lifetime. So this ended sixty years of speculation among family members about

his role.

He put his mark on a follow-up

article written by Tribune reporter James Doherty on April 15, 1951,

roughly twenty years after Capone's imprisonment, and it was he who had

nicknamed them “The Secret Six” in 1930. In his reminiscence, Doherty

maintained that he still didn't know who the Secret Six were. He stated,

"Really, I can't even swear they existed."

Eliot Ness refers to the Secret Six in his book,

but he never mentions any of them individually. Dennis Hoffman's 1989 monograph

on the subject, published by the Chicago Crime Commission, identifies perhaps

six individuals as being in the group, but he leaves out Barnard, which only

serves to illustrate just how secret the organization was.

**

Al Capone went to prison from October

24, 1931 to November 16, 1939, when he was released. He died January 25, 1947.

He was 48. For years he suffered from syphilis but he died from a stroke.

Julius Rosenwald died in 1932, Samuel Insull went on to lose his utilities

empire and be tried twice for fraud, although he was never convicted. My

grandfather went on to do more hospital construction at Children's Memorial and

Ravenswood Hospitals. Meagher, tough as nails, after he was shot asked to be

placed by a window next to the Lying-In job and directed construction from his

hospital room as he recovered from the gun-shot wounds. He wore with pride his

hat with the gunshot in it, but the hat ended up in his garage and vanished when

his wife moved after his death.

It was an exciting time for Barnard’s

children. Their father would go off to work with a police escort, and one time

when bent over to kiss his wife goodbye, a gun fell out of his shoulder holster,

banging on the floor. The kind of thing children would never forget.

And what of Eliot Ness? Ness, who

began his career as a credit investigator for Retail Credit, went on to clean up

the “Moonshine Mountains” of Kentucky, Tennesse and Ohio. Then he became

Director of Public Safety in Cleveland, where he established the Cleveland

Police Academy. He went on to jobs in the public sector as president of

Guaranty Paper Corporation and Fidelity Check Corporation. Ness died of a heart

attack in 1957 at the age of 54, two years before the popular series, "The

Untouchables," became a hit.

And who were the Secret Six? Dennis

Hoffman, in his monograph, offered the following:

U.S. Bureau of Investigation reports (1932) indicate that Robert

Isham Randolph, Julius Rosenwald, and Frank J. Loesch belonged to the Secret

Six. Interviews Randolph gave to the press after Capone's conviction, Randolph

disclosed that Insull and Rosenwald were in the Secret Six. Judge John H. Lyle

(1960), who was directly involved in the private war on Capone, named Edward E.

Gore, Samuel Insull, and George A. Paddock as members of the Six. Minutes of

Crime Commission Executive committee meetings (1931a) contain an admission from

Gore that he attended meetings of the Secret Six. Finally, Oscar Fraley, who

with Eliot Ness wrote The Untouchables, told the author that he was

"fairly certain" Randolph, Insull, Rosenwald, Loesch, and Gore were in the

Secret Six.

It seems likely that Randolph was a

spokesman for the group, and not a member proper. Insull and Rosenwald were

likely members because of their prominence and the funds they could add to any

such activity. After those, it gets murkier, probably Loesch and Gore, but to

any such list I add Harrison Barnard, who led the attack of Chicago businessman

to rid the community of the gangster Al Capone, and who is perhaps the only one

to have left a written record admitting that he was a member of the Secret Six.

He left his mark on an article in the Chicago Tribune written one year

before he died at age 80. (Of natural causes.)

SOURCES

Barnard, Burton W., Conversations with Author

Barnard, Harrison Bernard, Scrapbooks

Barnard, William B., Conversations with Author

Bergreen, Laurence, Capone: The Man and the Era, Simon & Schuster, c1994

Doherty, James, 'Curtains for Capone', The Chicago Tribune, April 15, 1951

Grant, Bruce, Fight for a City: The Story of the Union League Club of Chicago

and Its Times • 1880-1955, Rand McNally & Company, c1955 by the Union League

Club of Chicago

Hoffman, Dennis E., Business vs. Organized Crime, Monograph, published

by the Chicago Crime Commission, c1989

McDonald, Forrest, Insull, The University of Chicago Press, c1962

Meagher, Wayne, Conversations with William B. Barnard and the Author

Ness, Eliot with Oscar Fraley, The Untouchables, Julian Messner, Inc.,

c1957

Randolph, Robert Isham, Randolph Scrapbooks, Chicago Historial Society

-

Collier’s, “How to Wreck Capone’s Gang,” March

7, 1931

-

Examiner, “Capone Will Be Sentenced in Federal

Court Today; Goes to Prison Tomorrow,” July 30, 1931

-

Examiner, “I’m Through! Secret Six Licked Me,”

Says Al in Interview,” July 30, 1931

-

Cleveland News, “Capone’s Offer to ‘Police

Town’ Is Revealed Here by Randolph,” March 8, 1932

- The

Clevelander, “Secret Six,” Volume 6, Number 12, April, 1932

bullets hit

struck

Meagher in his chest, a third and fourth went through brim and crown

of his fedora, the other two struck the building. The job foreman, Slim

Ebert,

pulled him down

behind a pile of

bricks. According to the final edition of the papers that night, Meagher

was not expected to survive.

bullets hit

struck

Meagher in his chest, a third and fourth went through brim and crown

of his fedora, the other two struck the building. The job foreman, Slim

Ebert,

pulled him down

behind a pile of

bricks. According to the final edition of the papers that night, Meagher

was not expected to survive.